The recently published Committee Study of the Central Intelligence Agency’s Detention and Interrogation Program by the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence has received considerable attention in the media, for good reason. The report provides details on interrogation techniques used on terrorists thought to be involved in the 9/11 attack and other plots to kill American citizens at home and abroad. The “enhanced interrogation techniques” (EIT)[i] were based on behavioral theory that was not designed to elicit information, but instead was developed to study depression. Inducing “learned helpless” in detainees was thought to be a way to obtain information to avoid another attack like 9/11.

Learned helplessness is a psychological concept developed almost a half century ago by a psychologist, Martin Seligman, at Pennsylvania State University and his colleagues. Seligman was interested in depression and the developing of therapeutic behavioral interventions that might alleviate it. In order to study depression experimentally he needed an animal model that would allow investigation of various therapeutic interventions to ameliorate the induced state of learned helplessness.

The behaviorist tradition predicted that when presented with electrical shocks, dogs should avoid the aversive event whenever possible. Seligman found that by administering electrical shocks at random intervals he could induce a behavioral state in which the dogs would lie down and not attempt to avoid the shocks. In the second and most revealing experiment, Seligman placed subjects in a box with a low divider down the middle. On one side of the box the floor was electrified; on the other, it was not. When subjects previously shocked with no way to avoid the shock were placed in the new box they did not jump over the low divider to avoid the shocks. Selgiman’s experiments with administering electrical shocks to dogs produced results contrary to the widely held theory of behaviorism developed by B. F. Skinner. See Figures 1-4.

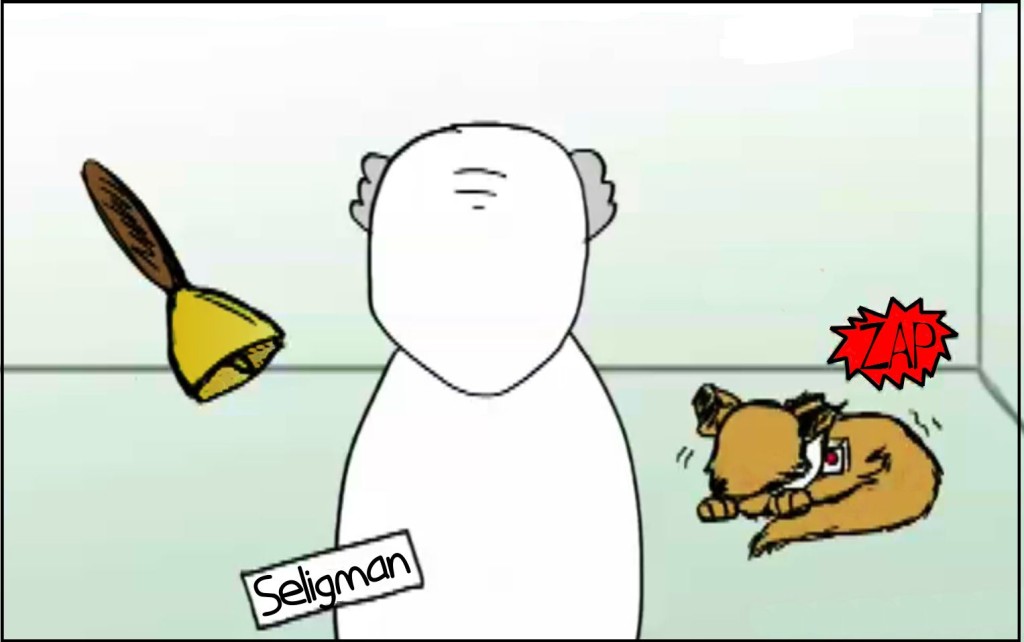

Figure 1: Seligman conditioned dogs to being shocked by ringing a bell. The dogs could not avoid being shocked and eventually just lay down and accepted the shock. Dogs, at the sound of the bell, would simply lie down, even if no shocks were administered. This is classical conditioning a la Pavlov.

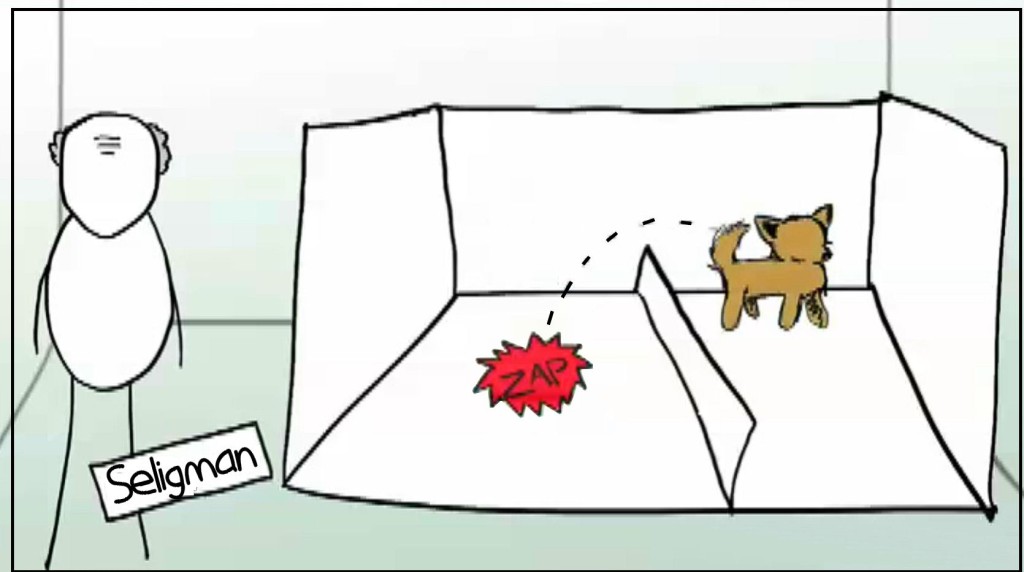

Figure 2: When dogs who had not been shocked were place in a divided cage with one side electrified they quickly avoided the shock and jumped over the barrier onto the non-electrified side. These results are fully consistent with the ideas of B.F. Skinner and the behaviorist tradition.

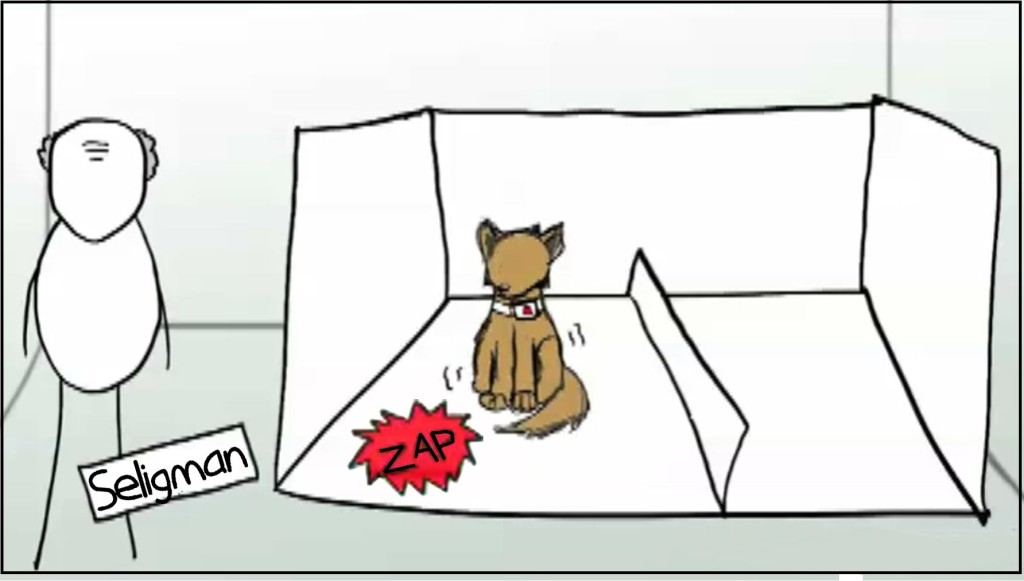

Figure 3: When dogs that had been previously subjected to inescapable shock were put in the box on electrified side, they did not jump over the barrier and avoid the shock.

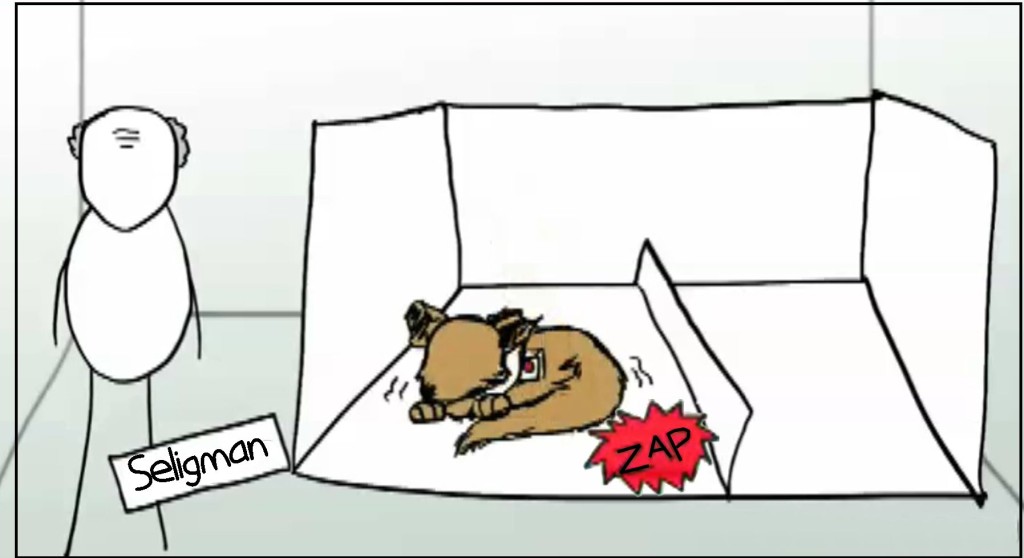

Figure 4: The shocked dogs lay down and accepted the shocks. This was the condition Seligman called “learned helplessness.” The dogs learned that escape was impossible and therefore they accepted the punishment.

This was a big deal in psychology at the time because these results were directly counter to Skinnerian behaviorism which predicted that when presented with an aversive stimulus subjects will avoid it. Moreover, the strength of the avoidance response should covary positively with the intensity of the aversive event. In this case, dogs should have jumped over the divider and the stronger the shock the more vigorously should the dogs jump over the divider. Seligman reasoned that subjects reached a helpless state because of unpleasant or even harmful circumstances administered at random intervals over which they had no control. When placed in a situation in which the dogs could have easily avoided being shocked, they had learned that it was impossible to avoid the shocks. Rather than avoiding the aversive event, subjects accepted the unpleasant circumstances. The lack of perceived control of the outcome led, in part, to a state that looked like clinical depression in humans. Seligman had developed an animal model of depression allowing him to continue his research in finding techniques that would overcome the induced psychological state.

Strange Bedfellows: The US Army and Martin Seligman

Seligman moved on from his comparative psychological research to focus on developing practical techniques for positive psychology, a type that helps individuals and organizations identify their strengths and use them to increase and sustain feelings of well-being. The buzz word here is resilience, and Seligman was teaching it.

When confronted with a steadily rising number of cases of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) as well as thousands of residual cases from the Vietnam War, the US Department of Defense (DoD) was highly motivated to develop better treatments. The Chief of Staff for the Army, Gen. George A. Casey, was interested in addressing PTSD problem by offering better treatment for the condition, as well as training in how one might avoid it, or at least ameliorate its devastating effects. In August 2008, Seligman was visited by Col. Jill Chambers to discuss the problems of soldiers returning from combat. This initial contact led to lunch with Gen. Casey, the chief of staff for the Army, and his advisors in early December 2008. Among the advisors present was Brig. Gen. Rhonda Cornum. Casey was concerned with the psychological well-being of troops and was searching for a program that would help him achieve his goal of improved psychological well-being for army troops.

Enter Martin Seligman. Casey was impressed with Seligman and his ideas about positive psychology and resilience, and gave Seligman 60 days to develop an outline for such a program. Oddly, the Surgeon General of the Army suggested that the program not reside in the Medical Corps, but be moved to education and training. It was thought that this would remove any stigma associated with psychological treatment and be better aligned with a universal training purpose. Seligman noted that his program, The Penn Resilience Program, was designed to teach the skills of resilience and positive psychology, with those who were trained then teaching these skills to their students. “The teachers of the Army are the drill sergeants, and they would become the teachers of resilience and positive psychology.” [1]

Figure 5: This certainly looks like a Drill Sargent that is a perfect candidate to become a Master Resilience Trainer, teaching recruits the basics of positive psychology. Warm and fuzzy, don’t you think?

The result was a three-year $125M program, the U.S. Army Comprehensive Soldier Fitness program with the main mission to use Seligman’s positive psychology to make soldiers more resilient on the battlefield as well as when they return home. The program was assigned to Brig. Gen. Rhonda Cornum, then the US Army Assistant Surgeon General for Force Protection, and she was made the Director of the US Army’s Comprehensive Fitness program. Seligman recognized the potential of the Army’s interest in his work and attempted to gain some additional professional credibility for his idea by organizing and editing a special issue of the American Psychologist entitled Comprehensive Soldier Fitness.[2]. Not surprisingly, Seligman included Rhonda Cornum [3, 4] and George Casey [5] as contributors to the volume.

Professional reaction to Selgiman’s ideas for the military met swift opposition. Lack of pilot studies on the effectiveness of this approach on military personnel when it had only been marginally successful on civilian subjects was troubling for some members of the psychological community. That Seligman’s resilience program was most successful when it was administered by highly trained professionals rather than staff recruited from the community raised concerns among many since Seligman had proposed to use of drill sergeants as “Master Resilience Trainers”. A series of articles in the American Psychologist offered stinging criticism of the Seligman’s program for the Army. [6-11]

Nonetheless, Cornum rammed a $31M training contract to Seligman through the Army bureaucracy on Casey’s behalf. [12] As a result, Seligman received a “no bid contract” from the US Army to teach soldiers to better cope with the psychological strain of multiple tours of duty. In Seligman’s terms he was teaching resilience and Casey was buying resilience. The Army awarded Seligman the contract because “there is only one responsible source due to a unique capability provided, and no other supplies or services will satisfy agency requirements.” Such contracts are allowed under very specific conditions, but are common at the DoD. Interestingly, Salon reported that there were other resilience experts at the University of Maryland and the Mayo Clinic who could have done the work. The moral of the story is that rank has its privileges and Casey got what he wanted, science or not. This blind single mindedness is a characteristic of the DoD, and it has had disastrous consequences for the US.

In Part 2

How could two clinical psychologists engineer an interrogation program that violated basic international law, proved ineffective in gaining counterterrorism intelligence, and cost taxpayers $80M? Easy, just ask the CIA. James Mitchell and Bruce Jessen amassed a fortune, failed to deliver on their contract, and tortured detainees that didn’t exist in places that weren’t on any map. Today, they are insulated from the consequences of their actions by the government that employed them in the first place. See Part 2 of this essay for details about how science was corrupted for personal gain and America threw its moral compass in the trash.

EO Smith

Latest posts by EO Smith (see all)

- Patriotism - 4 July, 2017

- The Super Sucker Bowl - 10 February, 2017

- Alternative Facts and Science - 24 January, 2017