I have taken a lot of pills lately, and recently, I was reminded of an Andy Rooney commentary on CBS News 60 Minutes. Rooney was the quintessential curmudgeon, and had the uncanny ability to find irony and humor in the most trivial details of life.

In the past, when you opened a new over the counter (OTC) medicine bottle, it was stuffed with cotton. It seemed like yards and yards of cotton could be stuffed into the tiniest of bottles. Instead of cotton packing, we still have medicine bottles that are usually one-third empty, with much of the space taken up by those little plastic cylinders that contain silica to keep the pills, tablets, or capsules dry. Typically, companies use desiccant cylinders that are only a millimeter or two smaller than the mouth of the bottle, so they not only fill up space but make it difficult to get pills out of the bottle. Inevitably, you try to shake a pill out of the bottle, but the desiccant cylinder plugs up the mouth of the bottle. If that is not enough, we also have tamper-proof caps with those little aluminum foil covers over the mouth of the bottle. You know the ones with the little tabs that are impossible to grasp. If you are like me, you just grab a sharp object, puncture the foil seal, and throw the desiccant cylinders as far as possible.

In the past, I was always amazed when I opened a new bottle of aspirin and pulled out 18 inches or so of rolled cotton. The cotton was clean and white and gave the impression that the contents were pure, unsullied, and full potency. That translated into confidence in the product. The wadded cotton was presumably to prevent the pills from chipping or breaking in transit. Broken pills are not esthetically pleasing and make it hard to regulate dosage. Chipping destroys the coating on pills, making them more difficult to swallow and potentially interfering with their timed-release properties. Therefore, the wad of cotton in your medicine bottle served at least two purposes, enhancement of the pharmaceutical elegance of the product (appearance and absence of physical deterioration or flaws), and preservation of the product.

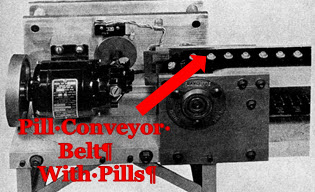

Which brings me to an interesting story about the problems inherent in quality control in the manufacture of drugs. The use of cotton in medicine bottles is just one of the measures that drug manufacturers use to ensure that their pills or capsules are intact and unbroken. As the demand for drugs increased along with technological innovation, drug manufacturers designed machines that could produce hundreds of thousands of pills per hour. No one wants to open a new bottle of pills and find that they are broken or chipped, so pharmaceutical elegance is a big deal in the pill business.

Can you imagine a more boring job than watching a conveyor belt moving thousands of pills an hour past you, and your job is to pick out the ones that are defective? I remember as a kid taking a tour of the local Coca Cola bottling plant. The first thing you saw as you approached the building through a huge plate glass window was an assembly line with workers inspecting a fast moving stream of Coke bottles to be sure they were not broken or otherwise unsuitable for use. If nothing else, this school field trip indelibly etched that picture in my mind, and provided a strong motivation to go to college.

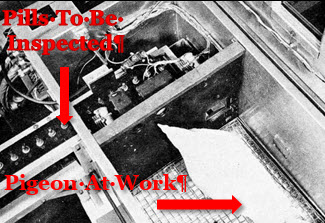

In order to solve the problems associated with quality control on assembly lines, particularly the monotonous checking jobs, a device was developed by Thom Verhave, a student of B.F. Skinner, and it reduced the error rate to less than 1% [1]. Verhave was employed by a pharmaceutical company that was wrestling with quality control problems. Not only did Verhave’s device make very few mistakes, it almost eliminated the need for human workers. Not only was the quality control issue solved, but costs were significantly reduced. As you can imagine, management of the pharmaceutical company was delighted when shown the initial prototype.

Verhave’s device relied on Columba livia domestica, the common pigeon for quality control. Pigeons were trained to peck a key when an irregularly shaped or cracked pill would come past on the assembly line. The pigeons were housed in an apparatus that isolated them from the conveyor belt. The pigeons were housed in such a way that they could see the conveyor belt through a window, and the key and food dispenser were isolated from the conveyor belt. A key peck would remove the defective pill from the conveyor belt, and when two pigeons worked together and were reinforced with food, errors were virtually zero. Management was taken aback. Such accuracy and precision was unheard of, using humans, but for pigeons it was a task to which they could be trained within one week.

However, the initial enthusiasm of middle level management was dampened by the response of the owners of the company. Can you imagine the public relations disaster if it got out that if competitors knew that there was quality control by pigeons? It would be a public relations nightmare. Verhave replied that hawks would work just as well as pigeons, and what could be better than quality control with the eye of a hawk. Anyway, today quality control is done with much more sophisticated scanning devices increasing production capacity and reducing errors. Somehow though, the pigeons were a very cool idea.

My final beef with the pharmaceutical industry for today is the tamper-resistant bottles used for all drugs. Consumers are told to “push down and turn to open”. I am sure that I am not alone in expressing frustration with safety bottles. Of course, you can request that your pharmacist substitute the tamper-resistant caps with the old fashioned pop caps, but more than once I have opened a package and found that I forgot to indicate my preferences. To add insult to injury, in many OTC medications there is that pesky problem I mentioned earlier – a further layer of “consumer protection” consisting of an aluminum foil cover hermetically sealed over the mouth of the bottle. Today many manufacturers are making the seals with a small tab that supposedly will allow one to grasp and in one sweeping motion remove the foil cover. To this claim I say nonsense. Most of the tabs are either glued to the side of the bottle or are so thin that it impossible to grasp. When that happens you have to resort to a sharp object to pry the foil away from the bottle. Generally, I resort to the “get a bigger hammer” school of home repair and reach for a knife to cut the foil from the mouth of the bottle.

I get it that the tamper resistant bottles are to safeguard consumers and they arose as a response to a number of deaths of children from poisoning, as well as the Tylenol murders in Chicago in 1982. In that event, seven people were poisoned after taking cyanide laced capsules that had been placed in Tylenol bottles on merchants’ shelves. The cyanide-laced Tylenol caused a massive recall of Tylenol by the manufacturer, Johnson & Johnson, of an estimated 31 million bottles, with a retail value in excess of $100M. Of course, poisoning has been recognized as a significant cause of death in children for many years and the Consumer Product Safety Commission reported that special packaging significantly reduced the medicine-related death rate of children under age 5.

Advocates of tamper-proof bottles and foil seals point proudly to the dramatic reduction in child poisoning fatalities, but there are always costs, even to the product with such obvious safety features. While there are no data to assess the cost to senior citizens of an inability to open tamper-proof medicine bottles, I wonder if poor eyesight, advanced rheumatoid arthritis, and reduced grip strength have not contributed to more than a few deaths among seniors. Of course, you could argue that those adversely affected by tamper-proof caps are at the end of their lives and the poisoning victims were just children, but this argument makes little difference if you are the senior that can’t get an aspirin bottle open at the first signs of cardiac arrest.

A study [2] of 1810 seniors found that 14% were unable to open a screw cap bottle, 32% a bottle with a snap lid, and 10% a blister pack, with women having greater difficulty than men. Given the technological advances made in the US in my lifetime, it seems to me that someone could develop packaging for pharmaceuticals that was difficult or almost impossible for a child to open, without requiring seniors to “get a bigger hammer.”

As I have said many times on this blog, it is about the money. Pharmaceutical manufacturers stand a far greater chance of being sued by the parents of children who defeated the tamper-proof packing, than from seniors who missed a dose of medicine because of contrary packaging. Like the recall of defective switches on so many GM cars, it is a matter of economics. If a sufficiently large number of seniors won lawsuits against a pharmaceutical company it is almost guaranteed that a safe and truly user-friendly medicine bottle would soon be in your nearest pharmacy.

- Verhave, T., The pigeon as a quality-control inspector. American Psychologist, 1966. 21(2): p. 109-115.

- Beckman, A., et al., The difficulty of opening medicine containers in old age: a population-based study. Pharmacy World & Science, 2005. 27(5): p. 393-8.

EO Smith

Latest posts by EO Smith (see all)

- Patriotism - 4 July, 2017

- The Super Sucker Bowl - 10 February, 2017

- Alternative Facts and Science - 24 January, 2017