What do chronic idiopathic constipation, irritable bowel syndrome, osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, painful menstruation, deep vein thrombosis, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, neuropathic pain, partial seizures, erectile dysfunction, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and dyspareunia (painful intercourse) have in common? All of these conditions can be cured if you buy into the claims of the medications advertised during your evening television newscast.

The images are aesthetically pleasing, the background music is soothing, and the actors are good looking. Spectacular vistas are interspersed with soft, almost gauzy scenes of people interacting with physicians, walking dogs, playing with grandchildren, walking on the beach, and gardening. We are led to believe that lifelong happiness, cure of chronic pain, weight loss, freedom from shortness of breath, and sexual satisfaction are just a pill away.

Direct-to-consumer advertising of prescription pharmaceutical agents that includes specific claims of their efficacy and safety is legal only in the United States and New Zealand. Direct-to-consumer-pharmaceutical advertising (DTCPA) is a fairly recent occurrence. In 1962, Congress granted the FDA authority to regulate prescription drug advertising. In 1981, Merck ran the first ads for a pneumococcal vaccine, Pneumovax, in Reader’s Digest. Since then, the pharmaceutical industry has waged a successful and highly profitable lobbying campaign to continue to relax regulations. Today we have ad wars for prescription drugs and a multi-billion dollar industry being waged on the national evening television newscasts.

The ads highlight the purported benefits of the drugs, and while the ads must include safety warnings, the warnings are not shown on the television screen, but are voiced over at a speed that makes them virtually unintelligible. In print, the warnings are often relegated to a type font and size legible only with a high powered microscope. The point is that pharmaceutical companies are following the letter of the law, but are not giving consumers a fair and balanced picture of the benefits and costs of particular drugs, despite their claims to the contrary.

The ads highlight the purported benefits of the drugs, and while the ads must include safety warnings, the warnings are not shown on the television screen, but are voiced over at a speed that makes them virtually unintelligible. In print, the warnings are often relegated to a type font and size legible only with a high powered microscope. The point is that pharmaceutical companies are following the letter of the law, but are not giving consumers a fair and balanced picture of the benefits and costs of particular drugs, despite their claims to the contrary.

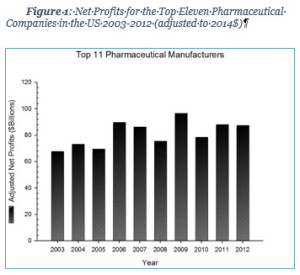

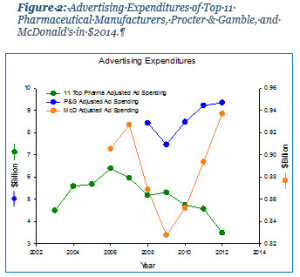

The pharmaceutical industry is big business by any standards, and DTCPA is a big part of a big business. Figure 1 shows the net profits for the top eleven Big Pharma companies for a decade.[1] Clearly, these international companies are doing quite well under the existing laws and it is in their best interest to see that regulations are not changed, but rather are relaxed  even more. To put this into sharper focus with respect to DTCPA, Figure 2 shows the advertising budgets for the top 11 pharmaceutical companies worldwide, compared with Procter & Gamble, and McDonald’s. The 11 top pharmaceutical companies spent, at their peak, more than the annual budgets of Delaware, South Dakota, Montana, West Virginia, Vermont, Wyoming, Mississippi, or New Mexico. They even outspent the fast food giant McDonald’s over the past several years. Clearly, advertising works.

even more. To put this into sharper focus with respect to DTCPA, Figure 2 shows the advertising budgets for the top 11 pharmaceutical companies worldwide, compared with Procter & Gamble, and McDonald’s. The 11 top pharmaceutical companies spent, at their peak, more than the annual budgets of Delaware, South Dakota, Montana, West Virginia, Vermont, Wyoming, Mississippi, or New Mexico. They even outspent the fast food giant McDonald’s over the past several years. Clearly, advertising works.

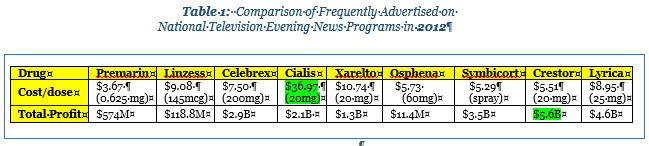

Given the advertising budgets of the 11 major pharmaceutical companies, it is important to understand the magnitude of financial rewards to Big Pharma. One of the bits of information not covered in DTCPA is the cost of the advertised medication. Table 1 is a sample of drugs frequently advertised on national evening news programs along with the cost per dose and the total profit that drug generated for its manufacturer. One would never know when watching the ad with the couple sitting in adjacent bath tubs, holding hands, looking into the sunset, that Cialis costs nearly $40 per 20 mg tablet, and generates $2.1B in profit for Eli Lilly and Company in 2012.  We are never told how Cialis “cures” erectile dysfunction”, nor that a loss in libido and a decrease in sexual activity are normal aspects of aging. We are left with the impression that ED is a disease that must be cured for total happiness. We are not told that Cialis may cause headache, stomach cramps, indigestion, acid reflux, flushing of the face and neck, blockage of blood vessels in the eye, heart attack, high blood pressure, stroke, seizures, abnormal liver function, and angina. Eli Lilly has successfully manipulated a generation of sexually deprived males into thinking that with Cialis, they can be ready in the “age of taking action.”

We are never told how Cialis “cures” erectile dysfunction”, nor that a loss in libido and a decrease in sexual activity are normal aspects of aging. We are left with the impression that ED is a disease that must be cured for total happiness. We are not told that Cialis may cause headache, stomach cramps, indigestion, acid reflux, flushing of the face and neck, blockage of blood vessels in the eye, heart attack, high blood pressure, stroke, seizures, abnormal liver function, and angina. Eli Lilly has successfully manipulated a generation of sexually deprived males into thinking that with Cialis, they can be ready in the “age of taking action.”

Crestor is a wildly profitable drug for reduction of cholesterol that is manufactured by AstraZeneca and generated over $5B in profits in 2012 alone. A current ad for Crestor seen frequently on national television is an excellent example of an ad creating a cure for a condition. The “super fan”, a middle-aged male, is captivated by the drug and is attired in hideous orange clothing and orange tennis shoes, talking on an orange “princess” phone in a room filled with various Crestor emblazoned items and orange furniture. He is seen with the family dog, also decked out in an orange sweater. In another scene, the “super fan” appears on the porch of his house looking fondly at the orange Jeep in his driveway. Of course, the star is an adult male and features the pathological identification some males have with sports teams and presumably with Crestor. The viewer is only briefly informed of the side effects, including constipation, heartburn, insomnia, depression, memory loss, myalgia, jaundice, dark urine, difficulty breathing or swallowing, and increased risk of diabetes. We are left with the admonition to “be down with Crestor,” need it or not.

Big Pharma argues that such advertising is good for consumers. Proponents claim that DTCPA informs, educates, and empowers patients to take control of their own healthcare. Big Pharma argues that the DTCPA encourages patients to contact a health care provider for medical advice and this increased patient/physician contact could promote discussion of lifestyle changes that improve patients’ health. Additionally, such conversations could strengthen a patient’s relationship with a clinician and lead to improved patient compliance. Supporters of DTCPA further argue that under-diagnosis and under-treatment of conditions can be identified and addressed through advertising messages. Moreover, the stigma associated with certain conditions and diseases is reduced through DTCPA (e.g., depression, erectile dysfunction), according to public relations messages from Big Pharma.

On the other hand, opponents argue that DTCPA misinforms patients by omitting key information about risk factors and side effects. They contend that DTCPA also minimizes the therapeutic effects of changes in lifestyle independent of prescription medication. DTCPA advertising often exceeds the eighth grade reading level, the level recommended for information distributed to the general public, and laypeople do not have the skills to evaluate the claims made in the ads. In one survey, 50% of the respondents thought that all ads were approved by the government, 43% thought that a drug had to be completely safe to be advertised, and 22% thought that a drug with serious side effects could not be advertised [2].

DTCPA overemphasizes the benefits of drugs and minimizes the risks. The benefits of drugs are given center stage and always presented in the most favorable light possible, while risks are often buried in large blocks of undifferentiated text or rapid voice over narrative, while more pleasant visual images are present. Studies have shown that where visual and verbal messages are discordant, visual messages predominate, causing poor processing of verbal information.[3] Clearly, Big Pharma has done its advertising homework.

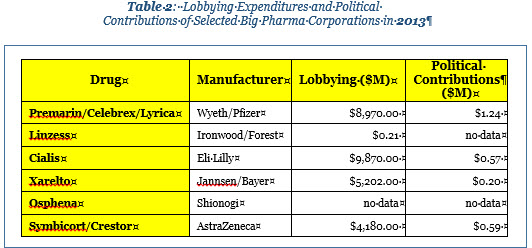

While the debate continues, DTCPA is another example of the power of lobbying efforts on social, as well as health policy. Big Pharma hires lobbying firms to influence elected officials in Washington to enact laws that are favorable to the industry. In addition to expenditures for lobbying, Big Pharma also makes direct contributions to political candidates. Table 2 summarizes a sample of heavily advertised drugs and highlights Big Pharma’s expenditure of funds on lobbying efforts and their direct contributions to political parties. The net result of the lobbying efforts is to continue the status quo and even reduce the amount of control the FDA can exert over DTCPA.

The goal of DTCPA is to encourage consumers to not only purchase more prescription drugs to treat conditions they might have not known they had, but to purchase particular drugs for therapeutic intervention. It is not by chance that the US allows prescription drug advertising. Regulations allowing television ads of prescription drugs are yet another way consumers are duped. Big Pharma goes to great lengths to portray itself as serving the greater good when, in reality, the only good they are serving is their profit margin. Big Pharma is notoriously slow to develop medications to treat low-incidence, non-profitable diseases, but quick to take advantage of conditions that accompany the normal aging process in a greying population, which is increasing with the aging of the baby boomers. DCTPA is not the only tool that Big Pharma uses to maximize profits at the expense of consumers, but the next time you turn on the evening news and you see an elephant walking on the beach, beware.

The reality is that if DCTPA were outlawed, there is no guarantee that Big Pharma would invest those funds in research into treatment for widespread, but less profitable diseases and conditions. More likely the reduced profits would simply be passed on to the stockholders in the form of smaller dividend checks, while upper level management continued to enjoy unjustifiable compensation. Isn’t capitalism great?

- Rome, E. Big Pharma pockets $711 billion in profits by price-gouging taxpayers and seniors. 2013; Available from: http://www.huffingtonpost.com/ethan-rome/big-pharma-pockets-711-bi_b_3034525.html.

- Connors, A.L., Big bad pharma: An ethical analysis of physician-directed and consumer-directed marketing tactics. Albany Law Review, 2010. 73(1): p. 243-282.

- Frosch, D.L., D. Grande, and D.M. Tarn, A decade of controversy: Balancing policy with evidence in the regulation of prescription drug advertising. American Journal of Public Health, 2010. 100(1): p. 24-32.

EO Smith

Latest posts by EO Smith (see all)

- Patriotism - 4 July, 2017

- The Super Sucker Bowl - 10 February, 2017

- Alternative Facts and Science - 24 January, 2017