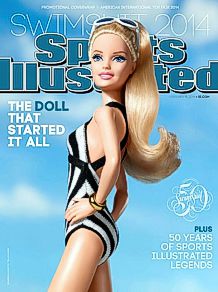

The Barbie doll is one of the most popular toys ever created. Today Barbie is sold in 150 countries at the rate of 3 dolls every second, and the manufacturer, Mattel, claims that over a billion have been sold worldwide. Barbie is a money-maker for Mattel, in no small part due to the plethora of sponsorship deals into which Mattel has entered with partners ranging from Nabisco and Oreo cookies, NASCAR, Major League Baseball, university football teams, and now, Sports Illustrated (SI). Recently, Barbie was featured on the cover of the SI swimsuit edition and represented a new low in the quest for profit on the part of Mattel and Time Warner. The partnership includes a promotional cover that claims that Barbie “started it all”, that is a modern definition of feminine beauty.

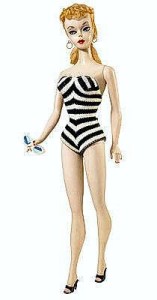

The SI campaign is centered on the 50th anniversary of the swimsuit edition with Barbie on the cover wearing a new version of the black and white swimsuit she wore at her introduction in 1959. The alliance of Mattel and Sports Illustrated is the latest in a long line of lucrative deals for Mattel. “Unapologetic” is the theme of the campaign, and has been the center of considerable attention in social media, as well as on a billboard in Times Square. Mattel boasts that Barbie is a legend, and argues that Barbie has been an undeserved target of criticism about her body from psychologists, nutritionists, physicians, as well as social critics. The SI cover feature gives Barbie, and the other “legends” that have appeared on the SI cover, an opportunity to own who they are, celebrate what they have done and be “#unapologetic,”[i] according to a statement from the Mattel Corporation. The SI Barbie is on sale at your local Target store for a bargain price of $19.99. Interestingly, the first Barbie sold for $3 in 1959 (about $28 in 2014 $).

Barbie was developed by Ruth Handler, the daughter of immigrant Polish Jewish parents (neé Moskowicz), who along with her husband, Izzy Handler, founded the Mattel Toy Company. Barbie was first marketed in 1959. The target market for Barbie dolls is girls 3-12 years of age. Girls typically have their first Barbie by age 3 and accumulate seven dolls over their childhood [1]. Annual sales of the Barbie Division of Mattel have averaged $1.5B per year for more than a decade, and since Barbie’s introduction, over 1 billion Barbie dolls have been sold. Barbie accounts for approximately 40% of Mattel’s total sales as well as 55% of their profit. It is safe to say that Barbie is an unbridled success by any standard.

Herein lies the problem and one of the main sources of controversy about Barbie over the last 3 decades. Barbie is marketed as an “aspirational model” to illustrate life possibilities to young girls, and the variety of occupations that Barbie has assumed is testament to the social conscience for women touted by Mattel. However, there is a more insidious side to Barbie and that is her physique. Critics have argued that Barbie represents a body image that is inappropriate at best, and pathological at worst. To attain Barbie dimensions, a five feet two inch, 125 pound female with 35-28-36 measurements would have to gain twenty-four inches in height, increase five inches in the bust, decrease six inches in the waist, and gain 3.2 inches in neck length. To put it a bit differently, our ideal would be seven feet two inches, with measurements of 40-22-36.[2, 3] A more conservative estimate of Barbie’s physique found that the probability of such a body conformation is less than .00001. [4] While Mattel describes Barbie as “full figured” she weighs only 110 lbs.[ii] and has a BMI of slightly over 16, a value that is an informal criteria for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa and universally classed as underweight to severely underweight by public health researchers worldwide. By most standards it is unlikely that Barbie would exhibit normal menstrual cycling given her absence of body fat.

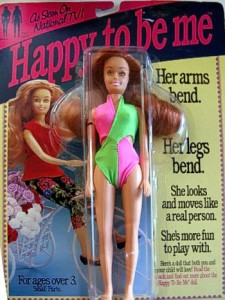

Interestingly, the 30th anniversary of Barbie heralded what some thought would be a healthier and more realistic portrayal of human females in the “Happy To Be Me” doll marketed not by Mattel, but by a competitor. This politically correct doll with a social agenda was poised to take over the market, but with her 36-27-38 measurements and a shorter neck, thicker waist, shorter legs, and larger feet, but the High Self-Esteem Toys Corporation fell flat on its face.[5] Customers were just not interested in a less attractive doll.

Interviews of junior and senior high school girls found that their perception of the ideal girl had a modest resemblance to Barbie: she is five foot six inches tall, weighs 110 pounds, wears a size five, and is able to eat whatever she wants and never gain weight. This does not sound like a cultural ideal to me, but rather like the making of a young woman with an eating disorder. Of course, the real question is the extent to which little girls perceive fashion dolls, such as Barbie, as an ideal to be achieved. The answer is that we do not know for sure, but considerable evidence suggests that such exposure creates expectations that are simply beyond the physical capabilities of most individuals.

Research in the area is suggestive, but not definitive. In a study of food consumption after playing with thin dolls, an average sized doll, Legos, or no doll (control), 6-10 year-old Dutch girls (n=117) who played with the average sized doll ate more food than girls who were exposed to the other experimental conditions.[6] In another study, 162 girls aged 5-8 were exposed to images of Barbie dolls, Emme dolls (normal proportions) or no dolls, then completed a body image assessment. Girls exposed to Barbie reported lower personal body esteem and greater desire for a thinner body shape than girls in the other exposure conditions. [7] Further confirmation of the acceptance of the Barbie ideal is found in a study of Playboy magazine centerfolds (n=647) from 1953-2007 found consistent perpetuation of the characteristics that are widely ascribed to Barbie. [8]

While suggestive, these studies do not unambiguously demonstrate the deleterious effects of playing with Barbie dolls, but coupled with the over emphasis in Western society on thinness the conclusion seems quite clear. The rationale for inclusion of Barbie on the cover of SI is suspect at best. Barbie represents and unattainable physique that is frequently touted as an ideal of female beauty. Couple that with the edition of SI that is renowned for images of bikini-clad models and you have a combination of images that doesn’t make sense. Is SI suggesting that its readers should purchase their very own Barbie? Are the models posing in the issue full-size living Barbie’s? The entire enterprise is objectionable on many levels. Once again corporate America has demonstrated that it cares little about the consequences of its actions. It is all about the money. Yes, this is an example of slutty capitalism[9] at its best or worst.

Bibliography

1. Grassel, K., Barbie aroud the world, in New Renaissance. 1999, Renaissance Universal.

2. Brownell, K.D., et al., Distorting Reality for Children: Body Size Proportions of Barbie and Ken Dolls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 1995. 18(3): p. 295-298.

3. Magro, A.M., Why Barbie is perceived as beautiful. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 1997. 85(1): p. 363-74.

4. Norton, K.I., et al., Ken and Barbie at life size. Sex Roles, 1996. 34(3/4): p. 287-294.

5. Anonymous, She’s no Barbie, nor does she care to be, in New York Times. 1991.

6. Anschutz, D. and R. Engels, The Effects of Playing with Thin Dolls on Body Image and Food Intake in Young Girls. Sex Roles, 2010. 63(9/10): p. 621-630.

7. Dittmar, H., E. Halliwell, and S. Ive, Does Barbie make girls want to be thin? The effect of experimental exposure to images of dolls on the body image of 5- to 8-year-old girls. Developmental Psychology, 2006. 42(2): p. 283-292.

8. Schick, V.R., B.N. Rima, and S.K. Calabrese, Evulvalution: The portrayal of women’s external genitalia and physique across time and the current Barbie Doll ideals. Journal of Sex Research, 2011. 48(1): p. 74-81.

9. Smith, E.O., When Culture and Biology Collide: Why We Are Stressed, Depressed, and Self-Obsessed. 2002, New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. 266 p.

[i] As evidence of the mass marketing of this edition of Sports Illustrated, an individual Twitter account was created with the hashtag #unapologetic.

[ii] 110 lbs is the weight set on bathroom scales marketed with Slumber Party Barbie, along with a book entitled “How To Lose Weight” with the simple message, “Don’t eat.”

EO Smith

Latest posts by EO Smith (see all)

- Patriotism - 4 July, 2017

- The Super Sucker Bowl - 10 February, 2017

- Alternative Facts and Science - 24 January, 2017