The association between light skin color and high social status has a long and distinguished history in Western society. In Victorian England, light skin was venerated and considerable effort was expended to keep women, particularly the upper class, out of the sun. Women in the Victorian period went to great lengths to avoid sun exposure and thus preserve pallid skin, a mark of status. Long sleeves, large hats, scarves, and parasols were employed as protective devices. Women in the monarchy were renowned for use of a variety of noxious chemicals to lighten artificially skin color, including regular application of lead based crèmes and pastes, arsenic, and other whitening powders.

In Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice (1813) the aristocratic Miss Bingley described Elizabeth Bennet as looking “brown and coarse,” because of her summer travels. [i] A proper lady, Miss Bingley implied, would strive to keep her skin pale and untanned. Protection from the sun as proper behavior for women is carried out in many artistic works by Claude Monet (e.g., Woman with a Parasol, Woman in the Garden Sainte-Adresse) and other impressionists.

Oceanside resorts and sea bathing became popular throughout Europe and North America in the late 19th century, however both women and men still covered up for modesty and for sun protection. In the 1920s, swimming emerged as a mainstream sport and along with it came a dramatic change in fashion. Rather than the bulky bathing dresses made from yards of fabric, women began wearing with form-fitting, sleeveless bathing suits.

Colonel C.O. Sherrill, Superintendent of Public Building and Grounds issued an order that bathing suits at the Tidal Basin bathing beach must not be over 6 inches about the knee. Bill Norton, the bathing beach policeman, measuring the distance between the knee and the bathing suit in the summer 1922. United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.cph.3b45864.

http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Col._Sherrell,_Washington_bathing_beach.jpg

By the 1920’s paleness was out and sun tanning had become a craze in Europe, and like all things fashion, the rest of the Western world followed. Part of the popularity of sun tanning was due in part to a widely publicized photograph of the cinnamon-toned Coco Chanel cruising to Cannes on the Duke of Westminster’s yacht. Additionally, Parisians were enamored with Josephine Baker, an American born French dancer, singer, and actress. She was the first African-American entertainer to achieve world-class status, starring at the Foiles Bergè. Then, as now, Paris was on the cutting edge of fashion and set the standard for much of Western society. These two women were leading figures in the transformation of the tanned skin of the working class, to the look of the fashionable and wealthy. Fashion followed suit in the 1920s with clothing coloration and cut that allowed plenty of sun exposure. Along the way, tanned skin became desirable, and a sign of lifestyle changes, not a sign of health.

Cornflakes and the Sun

Sunbathing received strong support from an unlikely source, and this support, combined with changing cultural preferences would launch the suntan revolution in the US. John Harvey Kellogg was a physician in Battle Creek, Michigan who gained considerable fame as the chief medical officer of the Battle Creek Sanitarium. The Battle Creek Sanitarium was a health resort based on health principles advocated by the Seventh-Day Adventist Church. Kellogg followed in the tradition of Sylvester Graham, an ardent dietary reformer, a devotee of vegetarianism, and the inventor of the graham cracker. Like Graham, Kellogg touted the health benefits of a vegetarian diet, abstinence from alcohol and tobacco, daily exercise, frequent enemas to rid the body of harmful bacteria, and phototherapy. Kellogg and his brother, Will Keith Kellogg, the business manager of the Sanitarium, were interested in developing foods that could be used as a part of the vegetarian diet for the patients at the Sanitarium. In August 1894, they accidentally left a batch of cooked wheat out and it went stale. Rather than discard the wheat, the brothers made a serendipitous discovery. They found that if pressed through rollers, instead of making a sheet of dough, the wheat mixture would form thin flakes. These were toasted and served to the patients and given the name granose.

The brothers experimented with other types of grains, and while John Kellogg was strict adherent to bland vegetarian diet, Will Kellogg was more of an entrepreneur. In 1906, Will Kellogg formed his own company, the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company, splitting with his brother over the addition of sugar to the recipe to make the flakes more appealing. Yes, added sugar was the cause of the rift between the brothers that would continue most of their lives.

In addition to diet, John Harvey Kellogg attempted to address what he considered other weaknesses of the human condition. He experimented with various contraptions to control such degrading human behaviors such as masturbation, constipation, flatulence. Along the way, he developed the Electric Light Bath Protocol detailed in his book Light Therapeutics [1].

He contended that the incandescent light bath had significant therapeutic effects on the circulatory system and was superior in its effects to the Turkish, Russian, vapor, and other forms of heating baths popular at the time. He argued that the Electric Light Bath could be regulated more precisely than fire-heated baths and radiant energy “passes through the skin and reaches the interior of the body at once.” Kellogg claimed his incandescent light bath was an effective treatment for renal disease, diabetes, obesity, dropsy, toxemia of chronic dyspepsia, rheumatism, and as a substitute for muscular activity in those with a sedentary lifestyle.

Kellogg was not the first to experiment with phototherapy. Niels Finsen, a Faroese physician, developed the first therapeutic light radiation that was successfully used to treat lupus valgaris. Finsen received the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine in 1903 for his research in phototherapy. Heliotherapy as it was also called, achieved some considerable popularity around the turn of the century, and provided a “scientific” basis for light exposure, setting the stage for the dramatic shift in attitudes about suntans. Sunbathing, as it was called, was supposedly able to cure ailments from acne to tuberculosis.

By the 1920s, attitudes had changed and paleness was out and sun tanning had become a craze. The widespread preference for darker skin challenged the basic assumptions of the cosmetic industry at the time – namely, good skin was light skin. Fashion followed suit in the 1920s with clothing coloration and cut that allowed plenty of sun exposure. Along the way, tanned skin became desirable, and was a sign of lifestyle changes and not a sign of health.

Biology of Tanning and Skin Cancer

Although highly valued, people quickly recognized the difficulty of achieving the desired bronze color. Too much exposure produced painful reddening of the skin, blistering, and sloughing of skin in affected areas. Protecting against the sun’s burning power requires understanding how sunlight affected skin.

The existence of light outside the visible spectrum was discovered in 1800 by William Herschel for infrared (slightly greater wavelength than visible light) and by Johann Wilhelm Ritter for ultraviolet (slightly shorter wavelength than visible light) in 1801. Later in the 19th century, scientists and physicians showed that ultraviolet (UV) radiation—not the sun’s heat—was responsible for “erythema solare,” the inflammation and reddening of the skin that occurred because of excessive sun exposure.

Further research identified specific UV radiation wavelengths that affect the skin’s surface. Ultraviolet light is electromagnetic energy with a wavelength of 400-100 nm[ii] and consists of three subunits (UV-A, UV-B, and UV-C). Of the three types of UV radiation, increasing in energy, UV-C is potentially most harmful to humans. However, UV-C is completely blocked by the ozone layer surrounding the earth along with the earth’s atmosphere. Of the remaining UV light that reaches the earth, 95% is UV-A and only about 5% UV-B. Scientists have discovered that UV-B is the most harmful, but UV-A is far from benign and is implicated in melanoma formation.

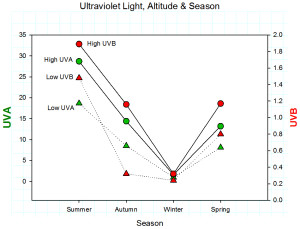

There are a number of factors that affect the amount of UV radiation reaching the earth’s surface:

- Season of the year and time of day – In the mid-latitudes, the summer months and a four-hour period around noon is the time of greatest UV exposure. In early morning and late afternoon, the sun is at a greater angle to the earth’s surface and hence the sun’s rays are less intense.

- Latitude – Equatorial areas have the most intense sun exposure and higher levels of UV radiation than more temperate climes. The sun is closer to the earth at the equator and for longer periods over the year.

- Altitude – Increasing altitude reduces of amount of atmospheric blockage of UV radiation. For every 3,300 ft. increase in altitude there is approximately a 10% increase in UV levels. That means that Hong Kong and Miami, as well as Pike’s Peak and La Paz, Bolivia receive approximately the same amount of UV radiation, all things being equal.

- Clouds and terrain – Generally, cloud cover blocks some, but not all UV radiation, while sand and snow reflect considerably more UV radiation than soil.

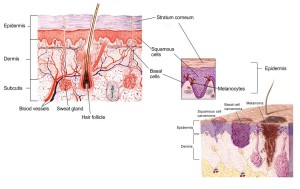

Our skin is the largest organ in the body and is much more than a sack to keep our internal organs contained, or a wrapper to keep pathogens out, or a canteen to store water. There are three layers of skin, but we will concern ourselves only with the outer layer, the epidermis. The epidermis is composed of five layers but only three are implicated in tanning and skin cancer. The outer layer consists of 20 or so layers of dead skin. The other two layers of the epidermis of concern for sun tanning are the squamous cells and the basal cells. The squamous cells are important because they are implicated in the manufacture of proteins that bind the skin cells together. The basal cells can be considered the stem cells of the skin and are the location of melanocytes, the pigment producing cells.

Sunburn is a radiation burn of living tissue. Our skin has a natural defense against radiation burns, a photoprotective pigment, melanin; present in human skin is responsible for minimizing UV damage. Mild sun exposure stimulates melanin production and produces a noticeable darkening of the skin, even in dark-skinned individuals. Overexposure to ultraviolet radiation causes direct damage to our skin. The inflammatory response we call sunburn is our body’s way of getting rid of damaged tissue.

UV-B light excites DNA and causes the production of a thymine dimer (lesion in backbone of the DNA molecule). Imagine the DNA double helix with the backbone on each side of the ladder consisting of a chain of bases connected together by covalent bonds. The rungs of the ladder are the appropriate complementary bases that link the two backbones with a hydrogen bond. UV-B radiation can break the hydrogen bond connecting the base pairs and that results in a break in the DNA chain, and subsequently disrupts DNA replication. Under normal circumstances the radiation-induced lesion is repaired by photoreactivation or nucleotide excision repair. However if the damage is beyond the capacity of our repair system, unrepaired dimers increase in frequency and are the cause of melanomas.

Unlike UV-B that damages the skin directly, UV-A causes the release of existing melanin from the melanocytes to combine with oxygen (oxidize) to create the actual tan color in the skin. UV-A is partially blocked by many sunscreens, and is blocked to some degree by clothing. UV-A is harmful, not by inducing direct DNA damage, like UV-B, but by producing chemically reactive oxygen molecules (reactive oxygen species) that damage DNA indirectly. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) is formed as a natural product of cellular metabolism of oxygen and is important in cell signaling and homeostasis. However, UV-A exposure will precipitate the formation of high levels of ROS, and this may result in significant damage to cell structures. The cumulative deleterious effects of high ROS levels is known as oxidative stress and is implicated in formation of carcinomas:

There are three different types of carcinomas that affect our skin.

- Squamous cell cancer is the second most frequently occurring type of skin cancer and occurs most often in areas exposed to direct sunlight. The long-term prognosis for squamous cell skin cancer like all cancers, depends on a number of factors (type, severity, patient health, accompanying disease), but is generally good with only 4% of squamous cell carcinomas metastasizing and becoming life threatening.

- Basal cell carcinoma is the most common type of skin cancer but rarely metastasizes. However, it can cause significant tissue damage and disfigurement. The prognosis for affected individuals is excellent if treated early. However, the reoccurrence rate is higher than with other skin cancers and each reoccurrence is more difficult to treat. Averages of 3.7 million people are treated for non-melanoma skin cancers in the US.

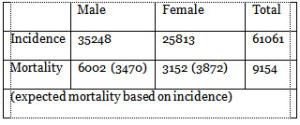

- Melanoma is a malignant tumor of the melanocytes, and is the least common of the skin cancers, but it is much more dangerous if not treated early. About three-fourths of the deaths from skin cancer are from melanomas, and are particularly prevalent in fair-skinned populations living in sunny parts of the world. More than 60,000 cases of melanoma [2] are reported each year and approximately 9,000 people die from it each year.[3]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention tracks the incidence and mortality of melanomas in the US population since of the skin cancers, they are the most likely to result in death. Basal cell and squamous cell carcinomas are not monitored. While men are diagnosed with melanomas about as frequently women, men die from melanoma almost twice as frequently as women (p<.05). It is likely that men engage in outdoor occupations much more frequently than do women. Men are less likely to seek early diagnosis and treatment for melanoma and men may have other conditions that exacerbate the lethality of melanomas.

Sunscreens

Australian dermatologist Charles Norman Paul published the first study connecting solar radiation to skin cancer in 1918, but his call to avoid “reckless exposure to sunlight” went unheeded for decades [4]. While a full scientific understanding of the effects of sunlight on human skin was decades in the future, entrepreneurs were quick to recognize a potential market.

Jean Patou, a wealthy French fashion designer, capitalized on the new tanning fad launching the first suntan oil “Huile de Chaldee” in 1927. According to advertising of the day, it was a tribute to the ancient civilization of Mesopotamia famous for its beautiful dark skinned people. Made of luxurious ingredients, Huile de Chaldee is a blend of orange blossom, amber and rose. There is little evidence that it aided in tanning or protected from UV radiation, but it must have smelled wealthy.

In 1935 that the first commercially successful sunscreen was marketed in the US. Eugène Schueller, founder of the

cosmetics firm L’Oréal, was the first to market a suntan lotion with a UV-filtering agent. The result, Ambre Solaire, was perfumed with roses and jasmine and packaged in a brown rippled bottle that would not slip out of the hand. Schueller was a marketing genius and in 1948 L’Oréal introduced the figure of “Suzy,” a shapely, tanned blonde-haired woman clad in what was then a risqué two-piece swimsuit. When reproduced as a life-sized cardboard cutout, “Suzy” was frequently stolen from pharmacies and seaside boutiques.

Other cosmetic and pharmaceutical firms followed suit, combining images of long-limbed, golden-toned bathing beauties with pseudoscientific claims for their products’ effectiveness. In the 1940s Skol and Tartan suntan lotions, two best-selling alcohol-based formulas, listed their impressive-sounding ingredients on the labels of their bottles in an effort to gain a marketing advantage. Skol touted 54% alcohol by volume, hexahydroxyethyl tannic acid, aluminum chloride, phenol salicylate or salol, menthol, and tertiary butyl cresol, among other ingredients. The tannic acid used was “an exclusive, patented form,” as claimed on the label that literally stained the skin, as well as clothing while providing only a mild degree of sun protection; salol was also a sun-screening agent of very limited effectiveness.

During World War II soldiers in the Pacific theater used sticky red veterinary petrolatum,

originally intended for animals, to shield their skin from the harsh sun. After returning home, airman and future pharmacist Benjamin Green cooked up “red vet pet” with cocoa butter and coconut oil on his wife’s stove, creating a moisturizing suntan cream that eventually became Coppertone.

“Little Miss Coppertone” arrived on the advertising scene in 1953, but commercial artist Joyce Ballantyne Brand redrew her in 1959, using her young daughter Cheri as a model because she “worked cheap and was convenient.” The iconic image shows a black cocker spaniel pulling down the swimsuit of a pigtailed toddler to display a pale bottom that contrasts with the tan on the rest of her body. The girl and dog appeared in print advertisements, in window displays, on eye-catching billboards—some motorized to repeat the motion over and over—and even as a 35-foot-tall lighted sign in Miami.[5]

The lure of a suntan led to the rise of indoor tanning salons. Given the widely accepted cultural value of a tan, it is easy to see that the possibility of such an appearance no matter the weather conditions had instant appeal. Friedrich Wolff introduced the first tanning beds into the US in 1979. Along with his brother, Jorg, Wolff tanning beds were the industry leaders. The critical resource for marketing indoor tanning is the lights, and Wolff patented a particular blend of phosphors for the fluorescent lights. Since their introduction, the Food and Drug Administration have regulated tanning beds, and regulations focus on lamp compliance, warning labels, and eye protection. Tanning lights emit UV radiation; about 97% UV-A and 3% UV-B and beds may be equipped with as many as 200, 100-200 watt lamps.

Each year about 28 million Americans visit an indoor tanning salon. The primary customers are young, white women. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has noted that indoor tanning increases the risk of skin cancer, and the risk increases with each additional tanning session. The younger you start the greater the cumulative effects. Nearly 1 in 3 white female high school students have used indoor tanning facilities, and over half report doing so frequently (10 ≥ times per year). Some young women are tanning by age 14 or younger. Recent studies have shown that people who tan indoors have a much, much higher risk of melanoma (74% greater) than those who never tan. Furthermore, the more time you spend in a tanning bed, the more likely you will develop a melanoma [6-8] .

Self-Tanning Agents

Given the increasing pressure on the tanning salon industry, it is not surprising that their revenue is not increasing. In fact, the segment of the market that seems to be benefitting from the regulations on tanning salons is self-tanning product manufacturing industry, marketing crèmes, lotions, and sprays to produce the perfect tan.

These topical products produce the desired tan by applying dihydroxyacetone (DHA) to the surface of the skin where it reacts with the amino acids in the dead skin cells to change color. The browning of the skin in response to DHA is well known by food chemists for it is the same reaction that causes an apple to turn brown after being sliced. Studies support the contention of the pharmaceutical industry that DHA is a safe additive to skin products. However, the most significant side effect is that after DHA application the skin is especially susceptible to UV radiation. DHA caused a nearly twofold increase in free radicals within one hour in subjects treated with DHA. Individuals who use DHA should avoid direct exposure to sunlight for several days after application. The same holds true for erythrulose, a chemical often used in combination with DHA in self-tanning products.

Americans are always looking for an easier way to do things, and the promise of a pill to lose weight, to regrow hair, or to improve you sex life has an irresistible appeal. In fact, there are pills that will produce the appearance of a suntan without any of the hassle of going to the beach or the expense of indoor tanning. Carotenoids are organic substances found in plants, some bacteria and fungi, but not in animals. In particular, carrots and tomatoes are rich sources of carotenoids that if ingested in large quantities will change skin color. Beta-carotene and lycopene are also chemicals implicated in self-tanning, along with tyrosine and the synthetic melanocyte-stimulating hormone (afamelanotide). The long-term effects of chronic or high doses of any of these compounds have been little studied and their side effects are unclear. Nonetheless, some have suggested that a long-term tanning agent that works without the deleterious effects of UV radiation is possible, but is far from reality at this time.

Economics, Politics & Tans

There are about 20K tanning salons in the US with a customer base in excess of 28M people. In 2013, the tanning industry was a $5B business. The recent recession slowed the industry growth, but with the slow rise in discretionary income, the industry is optimistic about modest growth opportunities in the next few years. To put those numbers into perspective, there are about 5K Wendy’s restaurants in the US, with annual revenue in 2013 of $2.5B. By any standards, the indoor tanning industry is big business.

The Affordable Healthcare Act landed a serious blow to the profit margin of the tanning industry because of the special tanning bed tax. Because of the widely accepted relationship between UV radiation from tanning beds and cancer, legislators felt that a tax was justified to discourage their use. Shortly thereafter California and Vermont made it illegal for anyone under 18 to use commercial tanning salons, and the World Health Organization has labeled indoor tanning devices as carcinogenic to humans.

Here is an industry that is marketing a product that imposes a heavy price on society. Like sugar-ladened soft drinks, tobacco, and alcohol, indoor tanning costs about $9.1 billion in medical care and productivity losses [9-11]. As with the tobacco industry, tanning salon owners have organized against any proposed regulations and have waged a vigorous lobbying campaign.

The trade group for tanning salon operators, the American Sun tanning Association, has mounted an aggressive PR campaign against the regulations. Taking a page from the tobacco industry playbook, sun-tanning lobbyists are attacking the credibility of scientific research as biased, since anti-tanning advocacy groups funded much of it. How can the results of studies be believed that are funded by organizations with a stake in the outcome? At the heart of the industry’s message is the idea that tanning critics such as dermatologists, oncologists, and even charities like the American Cancer Society are part of a profit-driven conspiracy[12]. This argument makes no sense. How are organizations that are dedicated to the reduction of the incidence and mortality from skin cancer be driven by a profit motive? Logic would suggest that if profit was the motivation, anti-tanning forces should be silent and let people engage in the dangerous behavior. The long-term future of indoor tanning salons is unclear, but be sure that they will not go down without a fight.

Today there are nearly a thousand sunscreen products on the market and while the sunscreen industry is relatively modest, it is part of the giant cosmetic and pharmaceutical industry. For example, Merck owns the popular Coppertone brand, Neutrogena is a corporate subsidiary of Johnson and Johnson, and Sun Pharmaceuticals Ltd. of Mumbai, India owns Banana Boat. Along with big Pharma, come lobbyists whose job is to see that there are as few legal impediments to marketing sunscreen products as possible. Of course, the way to achieve that goal is to see that legislators are elected that are not inclined to support regulations that would reduce industry profits. Through a variety of means, money is funneled to political campaigns and in some cases to candidates themselves.

One of the recipients of the Pharmaceuticals/Health Products industry largesse in the last election cycle was Fred Upton (R-Michigan) who received $108,500 from the PAC that represents the sunscreen industry, making him their top recipient. Oddly enough, Upton also happens to Chair the House Energy and Commerce Committee (HECC), the committee that decides the fate of the bills associated with sunscreen products. Similarly, the Vice Chair of the HECC is Marsha Blackburn (R-Tennessee) also received $63,500 from the same PAC. Of course, there is nothing illegal about these contributions, but from my perspective the entire lobbying conglomerate is ethically suspect.

Predictably, the vitriolic responses of the sun tanning and pharmaceutical industries to potential regulation are, of course, money. Even if sun tanning imposes costs on society, lobbyists argue that government intervention will reduce corporate profits and stifle creation of new jobs. Once again, as with most industries in the US, the goal is short-term profit maximization, not the long-term well-being of the society that makes their existence possible. Skin cancer be damned, full speed ahead.

When Culture and Biology Collide

Sun tanning is a classic example of our evolved biology and Western culture coming into direct conflict. We are programmed to behave in ways that are fitness maximizing, that is engage in activities that increase the probability of successful mating and production of viable offspring who, in turn, produce offspring themselves. One of the necessary ingredients to good health is Vitamin D, a substance important in the adsorption of calcium and phosphate and the maintenance of bone health. We synthesize Vitamin D by exposure to sunlight, as well as from our diet. Synthesis of Vitamin D from sunlight exposure is controlled by a negative feedback loop that prevents accumulation of toxic levels of Vitamin D if we are exposed to too much sunlight.

In the course of human evolution, our earliest ancestors arose in Africa and immigrated to other parts of the world. Anthropologists agree that migration into more temperate climes is associated with the lightening of the skin. Those populations inhabiting northerly and southerly latitudes would be exposed to lower levels of UV radiation and hence natural selection compensated for the reduced intensity by allowing greater adsorption by the skin. Of course, the way that was accomplished was to reduce the number of melanin producing cells in the epidermis of the population. By lightening the skin color, selection favored individuals producing biologically active levels of Vitamin D.

Therefore, in evolutionary terms it is easy to see that light colored skin is an adaptation to reduced intensity of UV radiation. For populations living in high latitudes, dark skin is not adaptive due to inadequate production of Vitamin D. Herein lies the fascinating part of human behavior. Why would people be willing to engage in and pay for a behavior that has been demonstrated to be fitness reducing? Continued and persistent tanning in the face of widespread knowledge about the dangers associated with UV exposure is a paradox.

A recent survey of college students’ perceptions about indoor tanning and UV light exposure found that 97% of current and past tanning bed users believed that skin cancer was a possible consequence of using a tanning bed. Moreover, a majority of both past and current tanning bed users did not think that tanning beds are safe (81% vs. 52%). In spite of knowledge of the dangers of UV radiation young white women continue to use tanning beds. The oft-heard axiom in public health is give people the information and they will act in ways that increase their health and well-being. That may be true for some people, but for some there is increasing evidence that an esthetic preference for a tanned appearance may not be all that is motivating behavior.

Some have suggested that for a segment of the frequent tanning population, those that tan outdoors or use tanning beds excessively are experiencing some rewarding effects independent of aesthetic preferences. It has been suggested that for some people, UV radiation may have some effects reinforcing effects on brain neurochemistry. A blind study compared regional cerebral blood flow in the brain of frequent tanners to UV exposure. Subjects were exposed to UV radiation and a sham control. In the experimental condition subjects experienced significant increased blood flow as revealed through MRI in the dorsal striatum, anterior insula, and medial orbitofrontal cortex. All of these areas associated with reward. These results suggest that UV radiation can directly stimulate areas of the brain in such a way that tanning behavior itself becomes rewarding [13], independent of aesthetic preferences.

Others have suggested that persistent, excessive tanning behavior is actually the result of UV radiation stimulating the release of β endorphins. In fact, one study of a very small number of frequent tanners and infrequent tanning controls found that when administered an opiate antagonist, naltrexone, 50% of the frequent tanners exhibited withdrawal-like symptoms, while none of the non-frequent tanners showed any withdrawal symptoms. This is certainly suggestive that among the frequent tanners there was an increase in endorphin production in response to UV radiation. The reinforcing properties of endorphins are well known and are implicated in a number of addictive behaviors. Considerable caution should be used in interpreting this study because of small sample size, but the results are suggestive that UV exposure could have reinforcing properties due to the release of cutaneous endorphins [14]. Other studies have failed to find the hypothesized relationship [15, 16], but further research is warranted.

Whether it is through direct excitation of areas of the brain associated with addictive behavior, or through the release of reward inducing neurotransmitters, it appears that a subset of the tanning population is engaging in the behavior in an addictive manner. Psychological tests have found that some frequent tanners exhibit loss of control in ways that are similar to alcoholics and other drug-addicted individuals. Further research is warranted if we are to understand why people continue to subject themselves to whole body exposure of a known carcinogen, and to develop appropriate interventions to minimize this harmful behavior.

The unsettling political aspect of sun tanning is the sharp disagreement over the role of government in protecting people from their own behavior. As with many aspects of human behavior, some argue that it is the individual who must take responsibility for their own actions regardless of the circumstances. Others argue that precisely because of their circumstances some people are unable to control their behavior and to avoid harmful behaviors. Arguments of regulation of tanning salons will have virtually no effect on this argument, it is clear that when left to their own devices sometimes people make costly, inappropriate, and injurious decisions.

If researchers are right and there are certain intrinsically reinforcing properties of UV exposure, the assertion that one day there will be a safe way to get a tan will likely be shown incorrect. Whether UV exposure is potentially addictive or not, we need to be mindful of the costs this behavior inflicts on individuals, but on society. If it is shown to be addictive, then it our responsibility to see that appropriate interventions and treatments are developed to help those afflicted.

Bibliography

1. Kellogg, J.H., Light Therapeutics; A Practical Manual Of Phototherapy For The Student And The Practitioner. 1910, Battle Creek, MI: The Good Health Publishing Co. 217 p.

2. United States Department of Health and Human Services& Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute. United States Cancer Statistics: 1999-2009. WONDER Online Database 2011 [cited 2013 September 13]; Available from: http://wonder.cdc.gov/cancer-v2009.html.

3. Jemal, A., M. Saraiya, P. Patel, S.S. Cherala, J. Barnholtz-Sloan, J. Kim, C.L. Wiggins& P.A. Wingo, Recent trends in cutaneous melanoma incidence and death rates in the United States, 1992-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2011. 65(5 Suppl 1): p. S17-25 e11-13.

4. Paul, C.N., The Influence Of Sunlight In The Production Of Cancer Of The Skin. 1918, London: H. K. Lewis. 57 p., 44 plates.

5. Boyd, J.E., A burning desire. Chemical Heritage, 2013. 31(1): p. 8-9.

6. Zhang, M., A.A. Qureshi, A.C. Geller, L. Frazier, D.J. Hunter& J. Han, Use of tanning beds and incidence of skin cancer. Journal Of Clinical Oncology: Official Journal Of The American Society Of Clinical Oncology, 2012. 30(14): p. 1588-1593.

7. Watson, M., D.M. Holman, K.A. Fox, G.P. Guy, A.B. Seidenberg, B.P. Sampson, C. Sinclair& D. Lazovich, Preventing Skin Cancer Through Reduction of Indoor Tanning: Current Evidence. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2013. 44(6): p. 682-689.

8. Lever, L.R.& C.M. Lawrence, Nonmelanoma skin cancer associated with use of a tanning bed (letter]. New England Journal of Medicine, 1995. 332(21): p. 1450-1451.

9. Bickers, D.R., H.W. Lim, D. Margolis, M.A. Weinstock, C. Goodman, E. Faulkner, C. Gould, E. Gemmen, T. Dall, A. American Academy of Dermatology& D. Society for Investigative, The burden of skin diseases: 2004 a joint project of the American Academy of Dermatology Association and the Society for Investigative Dermatology. J Am Acad Dermatol, 2006. 55(3): p. 490-500.

10. Machlin S, C.K., Kashihara D,, Health care expenditures for non-melanoma skin cancer among adults, 2005-2008 (average annual), in Statistical Brief 2011, Agency for Healthcare Rsearch and Quality: Rockville, MD.

11. Mariotto, A.B., K.R. Yabroff, Y. Shao, E.J. Feuer& M.L. Brown, Projections of the cost of cancer care in the United States: 2010-2020. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2011. 103(2): p. 117-128.

12. Huber, B. Burned by health warnings, defiant tanning industry assails doctors, ‘Sun Scare’ conspiracy. 2012; Available from: http://www.fairwarning.org/2012/08/burned-by-health-warnings-defiant-tanning-industry-assails-doctors-sun-scare-conspiracy/#sthash.ZPoS4FC4.dpuf.

13. Harrington, C.R., T.C. Beswick, M. Graves, H.T. Jacobe, T.S. Harris, S. Kourosh, M.D. Devous Sr& B. Adinoff, Activation of the mesostriatal reward pathway with exposure to ultraviolet radiation (UVR) vs. sham UVR in frequent tanners: a pilot study. Addiction Biology, 2012. 17(3): p. 680-686.

14. Kaur, M., A. Liguori, W. Lang, S.R. Rapp, J. Fleischer, Alan B.& S.R. Feldman, Induction of withdrawal-like symptoms in a small randomized, controlled trial of opioid blockade in frequent tanners. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2006. 54(4): p. 709-711.

15. Gambichler, T., A. Bader, M. Vojvodic, A. Avermaete, M. Schenk, P. Altmeyer& K. Hoffmann, Plasma levels of opioid peptides after sunbed exposures. British Journal of Dermatology, 2002. 147(6): p. 1207-1211.

16. Kaur, M., A. Liguori, A.B. Fleischer, Jr.& S.R. Feldman, Plasma beta-endorphin levels in frequent and infrequent tanners before and after ultraviolet and non-ultraviolet stimuli. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 2006. 54(5): p. 919-920.

[i] “How very ill Eliza Bennet looks this morning, Mr. Darcy,” she cried; “I never in my life saw any one so much altered as she is since the winter. She is grown so brown and coarse! Louisa and I were agreeing that we should not have known her again.”

However little Mr. Darcy might have liked such an address, he contented himself with coolly replying that he perceived no other alteration than her being rather tanned—no miraculous consequence of travelling in the summer. (Pride and Prejudice, 1813, Chapter 45, Book III, Chapter 3

[ii] A nanometer is equal to one billionth of a meter.

EO Smith

Latest posts by EO Smith (see all)

- Patriotism - 4 July, 2017

- The Super Sucker Bowl - 10 February, 2017

- Alternative Facts and Science - 24 January, 2017