The recent southerly shift of the polar vortex and the concomitant plunging temperatures prompted me to think about how we deal with cold weather. We have all heard the expression “Cold hands, warm heart,” in reference to an individual’s disposition or personality, but what about response to cold weather?

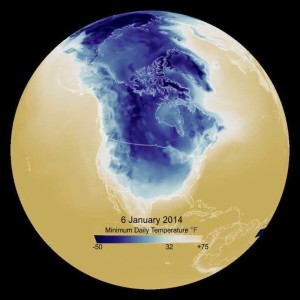

Figure 1: Southerly expansion of the polar vortex bringing record low temperatures to much of the US. NOAA.

Recently much of the US experienced record cold temperatures and “shift in the polar vortex” was heard in daily weather forecasts and was the lede on evening news. The cascade of cold, Arctic air that is usually contained well north of the continental US spilled across the border and invaded the Midwest and extended into the Deep South. See Figure 1. Record cold was experienced over much of the US, and the opening to almost every causal conversation was “Is it cold enough for you?”

So what about humans and cold weather? Today we can live in any environment, even outer space, with the aid of technology. Our big brains have made it possible for them (our brains), as well as the brain transport system, our bodies, to live in extreme environments (high altitude, heat, and cold). Because we wear a tropical climate wherever we go or create microenvironments that tropical, there is no place on the earth’s surface that is off-limits.

We know that the evolutionary line leading to modern humans arose in tropical Africa, although there are differing opinions whether it was in an open savanna or forested habitat. We know that humans emigrated from Africa and spread across Europe and Asia. It is hypothesized that inhospitable weather conditions limited migratory routes to more temperate climes, but with the acquisition of the purposive use of fire, many of the environmental constraints were lifted.

Fire not only provided a source of heat, but light as well, allowing the habitation of caves and rock shelters previously inhabited by a variety of human predators (e.g. cave bears). Moreover, control of fire fundamentally changed our diet in ways that some anthropologists believe allowed the development of our big brains. Simply put, foods that were previously unavailable, inedible, or even poisonous could become a regular part of the diet. Additionally, the mastery of making fire allowed a fundamental disruption in the typical day-night primate life-cycle.

There are a number of modern human populations that inhabit cold environments and have adapted to the cold, largely through technology. Eskimos are an example that comes to mind. By wearing the right combination of clothing these Arctic dwelling people, walk around in a tropical microclimate. Their ice shelters protect them from the wind and actually can be reasonably comfortable. The same is true with other populations inhabiting other arctic environs, like the Sámi, reindeer herders of Scandinavia. But are there examples of natural selection operating on human populations favoring individuals that exhibited physiological abilities to tolerate otherwise inhospitable climates?

Australian aborigines arrived in Australia about 50,000 or so years ago, and have remained largely genetically isolated from outside populations. Since immigration, they spread over the entire continent and today live in three main cultural areas. The Northern and Southern areas are considerably richer than the Central area, but hunting and gathering is the primary economic mode and aboriginal men have developed a reputation for their skill and resourcefulness.

Figure 2: Australian aborigines sleeping naked in near freezing temperatures. From: Berndt, C.H. & Berndt, R.M. 1968. Australian aborigines: Blending past and present. In: Vanishing Peoples of the Earth, National Geographic Society, Washington, DC, pp. 122-123.

An interesting aspect of the behavior of these hunter-gatherers is that while they wear clothing during the day, at night they sleep naked and use their clothing as a pillow. (See Figure 2). They will build a windbreak and several fires that they sleep in between. While air temperature in the Australian desert can drop near freezing, the aborigines sleep soundly through the night. Scientists use uninterrupted sleep as an excellent indicator of how well people are adapted to their environment. Studies of Australian aborigines have revealed some fascinating aspects of their physiology that allow them to tolerate nighttime temperatures near freezing.

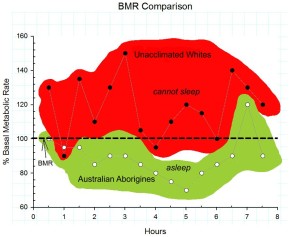

The classic studies were conducted over 50 years ago by human biologists interested in environmental physiology. [1] Skin temperature and basal metabolic rate were measured for a sample of aborigines sleeping naked out-of-doors, as well as white controls also sleeping in “bush mode.” Figure 3 shows a comparison of the BMR of both the aborigines and controls over one night. Australian aborigines are compared to unacclimated whites under identical conditions. Unacclimated white subjects responded to the cold temperature with a significant increase in their metabolism during the nighttime hours accompanied by shivering, increased tossing and turning, and insomnia. On the

Figure 3: Metabolism of Australian aborigines and white controls sleeping naked, out of doors in near freezing conditions. Redrawn from Scholander, et al. (1958).

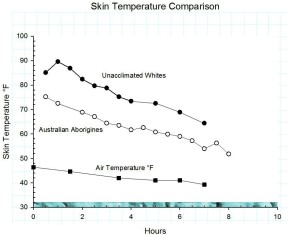

other hand, the Australian aborigines actually decreased their basal metabolic rate and slept soundly throughout the night awakening only to stoke the adjacent fires. Skin temperatures were also measured for subjects. In Figure 4 the comparison between Australian aborigines and controls is striking. While both the controls and the aborigines experienced significant skin cooling, the aborigines were able to tolerate skin temperatures near 40°F with no effect on sleep pattern. So what does this mean?

These and other studies suggest that Australian aborigines possess a suite of physiological adaptations that allow them to tolerate cold weather in ways that are not found in other human populations. That they do not elevate their metabolism in response to cold exposure as do most humans, and that they tolerate significant peripheral cooling makes them more similar to Arctic mammals, rather than other human populations living in cold climates. Clearly, the placement of multiple fires in a campsite allows the creation of a microclimate that is significantly warmer than the ambient temperature, but is of relatively little help when the wind is blowing. The primary adaptation is genetic, with the significant cultural addition of fire. Couple the energy conservation mechanisms with the ability to tolerate peripheral cooling makes the Australian aborigines an extraordinary example of evolution in action.

Figure 4: Peripheral skin temperatures in Australian aborigines and white controls in near freezing temperatures. Redrawn from Scholander, et. al, (1958).

Back to my origin proposition about cold hands and a warm heart, perhaps it should be revised in light of the Australian aboriginal example. The old saying should be “cold hands and cold heart, “ but that leaves much to be desired for romantics, but it does have a lot to say about evolution.

Bibliography

1. Scholander, P.F., H.T. Hammel, J.S. Hart, D.H. LeMessurier & J. Steen, Cold adaptation in Australian Aborigines. Journal of Applied Physiology, 1958. 13(2): 211-218.

EO Smith

Latest posts by EO Smith (see all)

- Patriotism - 4 July, 2017

- The Super Sucker Bowl - 10 February, 2017

- Alternative Facts and Science - 24 January, 2017