What do Spanish moss, Jack Daniel’s No. 10, Yoknapatawpha County, and Darwinian evolution have in common? The first three conjure up images of the American South, but it is Tillandsia usneoides (Spanish moss) that makes us think of expansive white columned mansions and giant southern live oaks. You’ve seen these trees, growing in the shape of a mushroom, sprouting virtually horizontal branches covered in long spidery threadlike fragments of greyish colored Spanish moss. But what does Spanish moss have to do with evolution? Actually, quite a lot as I will explain in a bit.

Spanish moss is a quintessential element in Southern Gothic literature, with writers using images of Spanish moss and antebellum mansions, along with redneck bars, pickup trucks, and trailer parks as familiar backdrops. While there is no shortage of the latter in the South, the days of widespread Spanish moss across the region are gone. Today, movie producers must hire locals to harvest moss from remote locations so that trees can fulfill the idealized image of how the South should appear. Redneck bars, pickup trucks, and trailer parks are considerably easier to find.

Spanish moss is neither a moss nor is it particularly Spanish. It is an epiphyte, a plant that grows on trees. Spanish moss is a bromeliad and is a relative of the pineapple. It derives no nutrients from the tree, but absorbs water and food directly from precipitation that has fallen on the leaves of its host tree species (foliar leaching). Spanish moss is naturally low in calcium and phosphorus, minerals critical to plant growth, and while most plants obtain these minerals from the soil, Spanish moss has evolved another technique. The long spindly threads of Spanish moss are ideal mineral collectors from the precipitation falling on the leaves and bark of host trees.

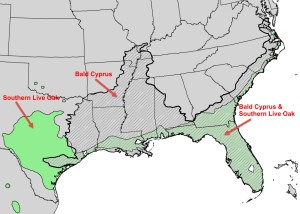

The distribution of Spanish moss is due the presence of host trees that are particularly good at foliar mineral leaching. Bald Cyprus (Taxodium distichum) and southern live oaks (Quercus virginiana) are favored because of high leaching rates of necessary minerals (calcium, magnesium, potassium and phosphorus). While Spanish moss can grow in other trees, (pecans (Carya illinoiensis), pines (Pinus spp.), and even on telephone lines (Linus telephoniensis),[i] the distribution of Spanish moss is largely dependent on live oaks and bald Cyprus. Spanish moss lives from coastal Virginia, and South Carolina all the way to Texas. In fact, the distribution of Spanish moss continues all the way to Argentina.

Now, what does a discussion of Spanish moss have to do with evolution? Actually, quite a lot. Plants and animals act out evolutionary scenarios every day in an attempt to maximize their genetic representation in future generations. There is no reason to think that Spanish moss, live oaks, or bald Cyprus are any different. So why is Spanish moss not more successful, given that garnering nutrients is not a problem?

Distribution map for Bald Cyprus and Southern Live Oak. The crosshatched are is the distribution of Bald Cyprus, The green area is the distribution of Southern Live Oak. The green crosshatched area is their distribution overlap.

Bald Cyprus live in the Mississippi River Valley drainage basin, along the Gulf Coast, and mid-Atlantic coastal plain. Bald Cyprus was a favored species for boats, flooring, cabinetry, caskets, and fence posts because of its resistance to rot of the mature hardwood. Their popularity in the past has significantly reduced their numbers today. This along with their slow growth, and their affinity for wetlands, are all factors reducing their profitability to loggers.

Southern live oaks grow well in salty soils and shady environs. They are vulnerable to freezing conditions, acid rain, insect infestation, and oak wilt fungal infection. Historically, their wood was used in shipbuilding for its hardness and durability. In fact, the hull of the USS Constitution, nicknamed “Old Ironsides” for her resistance to cannon fire from the HMS Guerriere during the War of 1812, was made from southern live oak cut from Gascoigne Bluff on St. Simons Island, Georgia, and milled nearby. Like Bald Cyprus, the southern live oak is not harvested for timber today. However, it does – like the Bald Cyprus – play an important part in ecology of its native habitat.

There are many factors that contribute to the diminished numbers of these two quintessential southern species, but a significant contributor to the disappearance of live oaks and bald Cyprus, and hence, Spanish moss, is not an act of nature. Rapacious development has decimated their habit. These trees, along with many others, are systematically being destroyed for construction of roads, utilities, as well as residential and commercial development. There is no way that evolved patterns of reproduction in either Spanish moss, southern live oaks trees, or bald Cyprus can succeed when faced with chain saws and bulldozers.

So while readers of southern fiction will continue to enjoy images conjured up by William Faulkner, Harper Lee, Flannery O’Connor, Tennessee Williams, and others, the reality of Spanish moss, bald Cyprus, and southern live oaks is another matter. Habitat destruction will limit the distribution of Spanish moss to areas that are unsuitable for development, at least in the short run. Favored host tree species and Spanish moss will be restricted to remote areas where only Spanish moss aficionados and fans of Southern Gothic literature are willing to hike or paddle.

Though I find Spanish moss draped live oaks and bald Cyprus enchanting, I am not making a special plea for the protection of these two host tree species or the protection of any single species. Any student of evolution knows that the ultimate fate of all species is extinction, and that is true for humans, as well. The campaigns to save individual species (e.g., the Alabama cavefish; Speoplatyhinus poulsoni, the Alabama beach mouse; Peromyscus polionotus ammobates, the Alabama cave shrimp; Palaemonias alabamae, or the Alabama canebreak pitcher plant Sarracenia rubra alabamensis)[ii]; or high visibility, signature species like the West Indian manatee, Trichechus manatus) will be unsuccessful in the long run due to avarice and greed. The destruction of the habitat of these endangered species is virtually assured at the hands of developers, eager for profit. Yes, capitalism will trump any effort to save any endangered species, but more importantly, it will also decimate the habitat in which they live.

It is safe to say that in the not too distant future, live oaks and bald Cyprus festooned with Spanish moss will be just a memory, but a fine memory for sure. When that happens, we can always return to Faulkner to summon images of this quintessential Southern plant.

Sources

- Adams, D. 2007. Spanish moss: Its nature history and uses. http://www.beaufortcountylibrary.org/htdocs-sirsi/spanish.htm

- Ball, J., Live oak: The ultimate southerner. American Forests, 2003. 109(3):44-47.

- Callaway, R. M., K. O. Reinhart, S. C. Tucker, and S. C. Pennings. 2001. Effects of epiphytic lichens on host preference of the vascular epiphyte Tillandsia usneoides. OIKOS 94: 433–41.

- Carocci, M., Clad with the ‘Hair of Trees’: A history of Native American Spanish moss textile industries. Textile History, 2010. 41(1):3-27.

- Garth, R.E., The ecology of Spanish moss (Tillandsia usneoides): Its growth and distribution. Ecology, 1964. 45(3):470-481.

- Krulik, J., Varieties of Spanish moss. Journal of the Bromeliad Society, 2008. 58(6):272-274.

- Schlesinger, W.H. and P.L. Marks, Mineral cycling and the niche of Spanish moss, Tillandsia usneoides American Journal of Botany, 1977. 64(10):1254-1262.

- Schneider, K., Trying to resurrect shades of the Old South. New York Times, 1990. 140(48444): 1.

- Speck, F. G. 1941. A list of plant curatives obtained from the Houma Indians of Louisiana. Primitive Man 14: 49–75.

- Suriel, R.L., Spanish moss: Not just hanging in there. Science Activities, 2010. 47(4):133-140.

[i] Spanish moss will colonize other tree species and some stationary objects in hot, humid climes.

[ii]. Yes, there are real endangered species, even in Alabama.

EO Smith

Latest posts by EO Smith (see all)

- Patriotism - 4 July, 2017

- The Super Sucker Bowl - 10 February, 2017

- Alternative Facts and Science - 24 January, 2017